[ad_1]

Women are the primary decision-makers of family health care decisions in the United States. Yet health inequity is still prevalent here and worldwide, potentially impacting the care for all women, and particularly for women in underserved communities and among Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC).

From access to screening to the quality of health care women receive, these disparities can lead to potentially life-threatening delays in diagnosis and treatment of disease. The importance of focusing on improving health care access and strengthening the capacity of health systems to provide preventive care and routine diagnostic screening for all patients, especially the most vulnerable, cannot be overstated.

There are, unfortunately, far too many examples of the ways in which women’s health has been underfunded, under-researched, and underserved. A recent Harris Poll conducted on behalf of BD has brought forward still more.

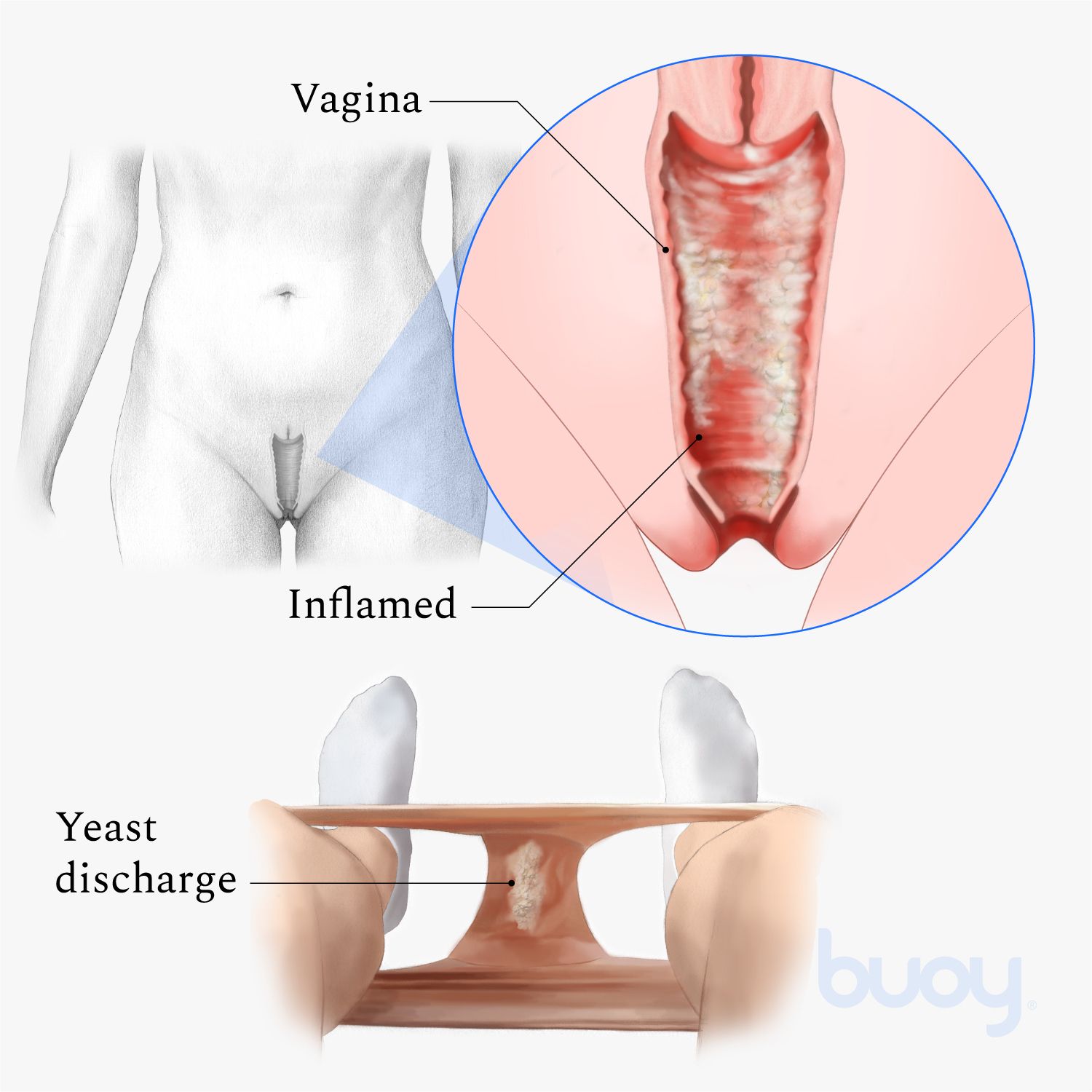

While more than two-thirds of women report having had or thinking that they had a vaginal infection or yeast infection, only 37% said their health care provider was able to diagnose their symptoms and prescribe the appropriate treatment after one visit. And when we look at the data through the lens of ethnicity, the results are even more troubling.

The study shows that that less than a third of Black women (29%) say their health care provider was able to diagnose their symptoms and prescribe appropriate treatment after one visit. The figure drops even more (23%) among Hispanic women. That disparity is particularly acute compared to white women, 42% of whom reported successful diagnosis and treatment after one visit—a figure which itself is still disappointingly low.

A misdiagnosis means inappropriate treatment recommendations — either undertreatment or overtreatment. A person might be asked to make return visits to the doctor that aren’t necessary, and that can be a barrier to access if a woman is juggling multiple jobs, financial hardships, childcare demands, or if there isn’t a doctor or clinic conveniently located.

Among women who have ever had or thought they had a vaginal infection, those disparities in getting health care appointments were shown to be more significant for Hispanic women, who were three times more likely than white women to say it took a long time to get an appointment (15% vs. 5%) and four times as likely to say that it took several visits to their healthcare provider to find an appropriate treatment (16% vs. 4%).

And late last year, another BD-sponsored Harris Poll indicated a significant gap in women’s familiarity with the primary causes of cervical cancer (i.e. HPV) as well as the most effective means of prevention (i.e. vaccination and regular screening).

That study highlighted a knowledge gap amongst Hispanic and Black women. Hispanic women are 2.5 times more likely than non-Hispanic white women to say they delayed getting a Pap test because they were afraid it would hurt, and Black women are almost three times more likely than white women to say they have no idea how often they are supposed to get a Pap test.

The most recent poll indicated that about one in 10 Asian women (12%) have never had a gynecological exam, similar to Black (10%) and Hispanic (11%) women; figures which again are about three times less the rate reported by white women.

If we consider convenience as a factor in health care access, self-collection becomes a viable and compelling option. Last year’s Harris Poll found that 79% of American women say they would be interested in using a self-collection kit for HPV or cervical cancer screening, an alternative form of screening that allows women to collect their own sample.

Self-collection is already in use around the world and in the U.S. (for testing in physicians’ offices, specifically), including for the BD Vaginal Panel which can test for multiple common types of vaginitis using only one swab and the BD CTGCTV2 test which detects the three most prevalent non-viral sexually transmitted infections. And self-collection for HPV testing, including the BD Onclarity™ HPV test, is approved and available now in many countries. A report recently published by the Biden Administration’s Cancer Panel seeks to accelerate this effort in the United States by calling on developers to validate self-sampling and on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve those claims.

Self-collection options are just one way the industry can do its part to improve access. Our diagnostic instruments and assays have been able to provide a direct impact on women’s health, from STI testing to cervical cancer screening. But our responsibility goes beyond developingmeaningful health care technologies; we must help ensure these innovations are accessible to more people. We have a responsibility to address these issues head-on, using our scale and influence to drive continuous improvement across our society’s biggest challenges.

Our industry can have a clear and meaningful societal impact, but as the saying goes, “If you keep doing what you’ve been doing, you’re going to keep getting what you’ve already got.” The health care industry needs to do more than put health equality at the top of its agenda; we need to take bold action together, now and every day.

The findings of these polls deepen our understanding and serve to reinforce our commitment to change. We applaud the work of the recently formed Congressional Social Determinants of Health Caucus and look forward to working in partnership with this collection of lawmakers to enact real and effective change within our communities and actively reduce longstanding disparities in care.

About the Author: Brooke Story is Worldwide President of Integrated Diagnostic Solutions at BD.

[ad_2]