There is a moment, several chapters into Elizabeth Winder’s “Parachute Women: Marianne Faithfull, Marsha Hunt, Bianca Jagger, Anita Pallenberg, and the Women Behind the Rolling Stones” that quietly justifies the book’s existence. In the biographical introduction of the section about aspiring R&B artist Marsha Hunt — before her life is rerouted by bearing Mick Jagger’s first child — Hunt’s life story stands in contrast to the sections that have come before it. While the preceding chapters offer layered accounts, contemporaneous press coverage and bits of gossip, Hunt’s chapter offers no supporting quotes, no Rashomon-like perspectives refracted through the lens of LSD. Instead, Winder offers a single-sourced account of Hunt’s life, culled from Hunt’s memoir. Hunt’s solitary voice underscores the sad fact that for the countless books documenting every facet and travail of the Rolling Stones, “Parachute Women” is the first to narrativize the collective experiences of the consorts and wives who shaped the musicians. Winder spotlights how the vast influence of these women on the Stones has largely been hidden in the shadow of the band’s monolithic mythos.

The women who shaped the Rolling Stones finally have their moment© Hachette

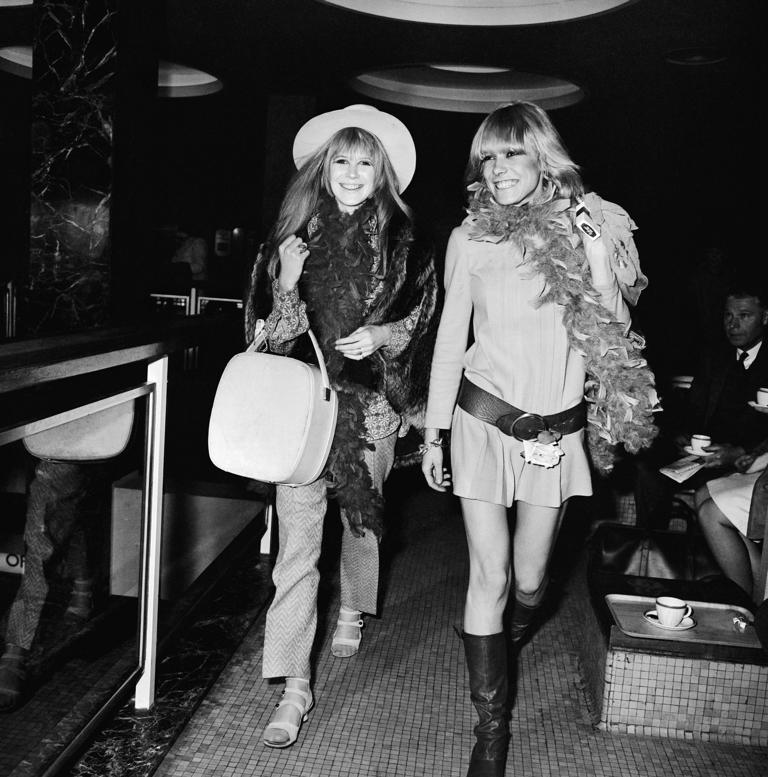

“Parachute Women” is a step toward according these women their rightful place in music culture, most especially Anita Pallenberg, who until now has typically been relegated to groupie icon. The German-Italian bon vivant and artist was a romantic partner to Brian Jones and Keith Richards, and a creative confidante and paramour to Mick Jagger (he called her “the sixth member of the band”). Yet, as Winder argues, it was Pallenberg’s unassailable style, laissez-faire hedonism and worldly air that imbued the laddish lambs with louche cool. She was a larger-than-life mentor, introducing them to all that would define them, from occultism and feather boas to skull rings and hard drugs; the band’s image mirrored her countercultural glam. Pallenberg was so vital to Richards in particular that, whenever she was offered a film role, Richards would counter her salary and beg her to decline and stay by his side. She always refused his offer.

Pallenberg’s friend, Marianne Faithfull, claims a significant stake in the creation of Mick Jagger. When then-teenage pop star Faithfull moved in with the frontman in 1966, his intellectual diet was supermarket pulp fiction. Faithfull gave him a proper education on Beat poets, Bob Dylan, history, mysticism, sexual adventure, French New Wave film and fashion, and routinely took him to the ballet. Her insistence that he read “The Master and Margarita” yielded the song “Sympathy for the Devil.”

As “Parachute Women” documents, proximity to the Glimmer Twins came at a high price. After Faithfull was infamously caught up in Mick and Keith’s February 1967 drug bust clad in nothing but a sheepskin rug, paparazzi played up the 20-year-old as a defiled English rose. The next morning the Evening Standard headline read: “STONES ARRESTED: NUDE GIRL AND TEAPOT.” The Stones management seized the opportunity and used the corruption of Faithfull’s angelic image as testament to the Stones’ rock-and-roll influence, a badge of what bad boys they were, even though it created significant personal and professional collateral damage for Faithfull, wrecking her music career. Winder writes: “In the end, the forces that demonized Marianne and exalted Mick were one and the same. It wasn’t just moral panic over ‘degenerate youths’ … It was rock culture itself.”

Pallenberg with Keith Richards at Richards’s home in London, 1969. She was a girlfriend to Richards and a mentor to all the Rolling Stones.© Peter Kemp/AP

Chapter after chapter, Winder shows how these four women persevered, in the face of indignity and trauma. Jones’s violent assaults on Pallenberg that went unremarked upon by the rest of the band; Jagger’s refusal to accept paternity of the child he convinced Hunt to have and his callous treatment of Faithfull after the loss of their daughter — it’s a grim indictment of the band and their enabling coterie. Winder is deeply empathetic to these women, and her disgust for the band and their yes men is plain, but she is hardly a critical biographer; she leaves the reader to draw their own judgments (which is not hard to do).

Faithfull’s best-selling memoir is the primary source for the chapters on the singer’s life and times with Jagger, and her ribaldry and bon mots (“there is nothing truly mythic or tragic about Mick”) dull the rest of “Parachute Women” in comparison. Winder’s tight aperture on Hunt, Pallenberg, Faithfull and briefly Bianca Jagger is a welcome reprieve from the typical Stones hagiography, which casts Mick and Keef as self-made gods and rationalizes damage done by them as “only rock-and-roll,” as the song goes. But her dedication to these daring, free women comes at the cost of needed context about the Stones and their trajectory. Though some assumption of reader knowledge of the Rolling Stones from 1967 to 1975 can be forgiven, the book is at times disorientingly myopic.

Jagger marries Bianca Perez-Mora Macias in Saint Tropez, France, on May 12, 1971.© AP/AP

Lacking a broader timeline of how the world of music and culture was shifting, Winder writes that “times had changed,” but not how or for whom, or whether music biz “misogyny” was to blame. Additional context for details would have been helpful, too: Names appear without introduction; unattributed and uncited quotes abound, leaving the reader to wonder who is speaking. Winder occasionally makes a meal out of a breadcrumb trail (“photographs of the weekend reveal a frolicsome sensuality”) to keep the narrative afloat, but it evinces just how criminally under-documented these women have been. “Parachute Women” is a valiant start, one that stokes a hunger for a deeper dive into the full lives of these four women.