On the Works of Farnaz Farid

– Ümit İnatçı

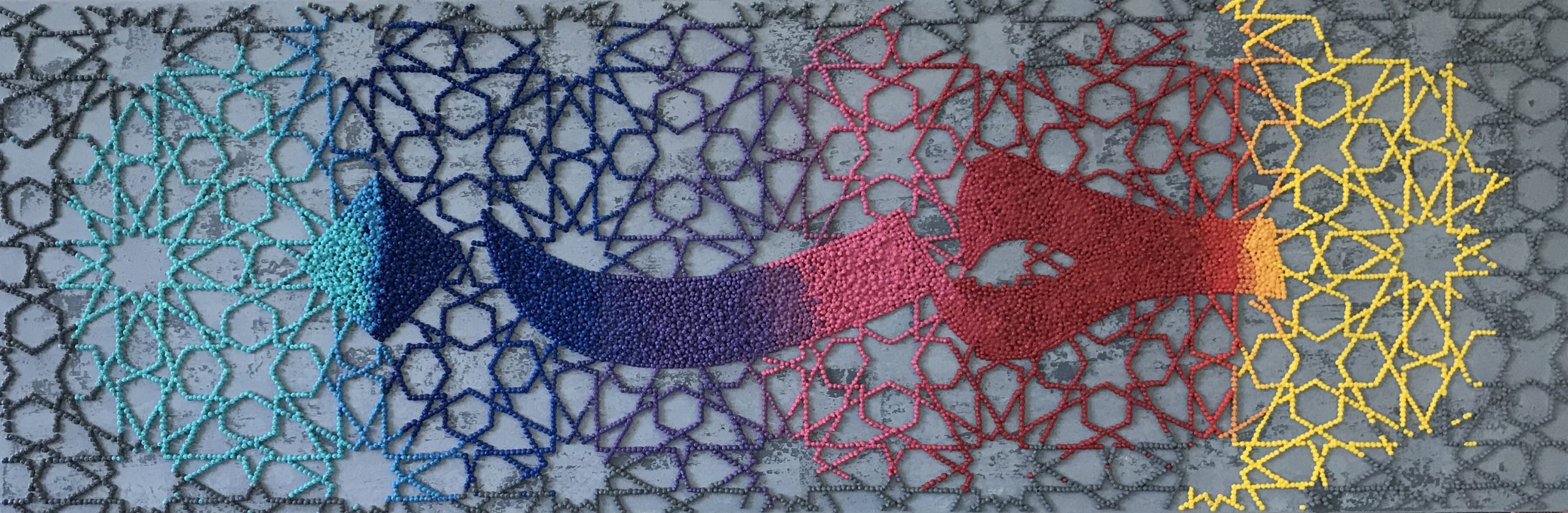

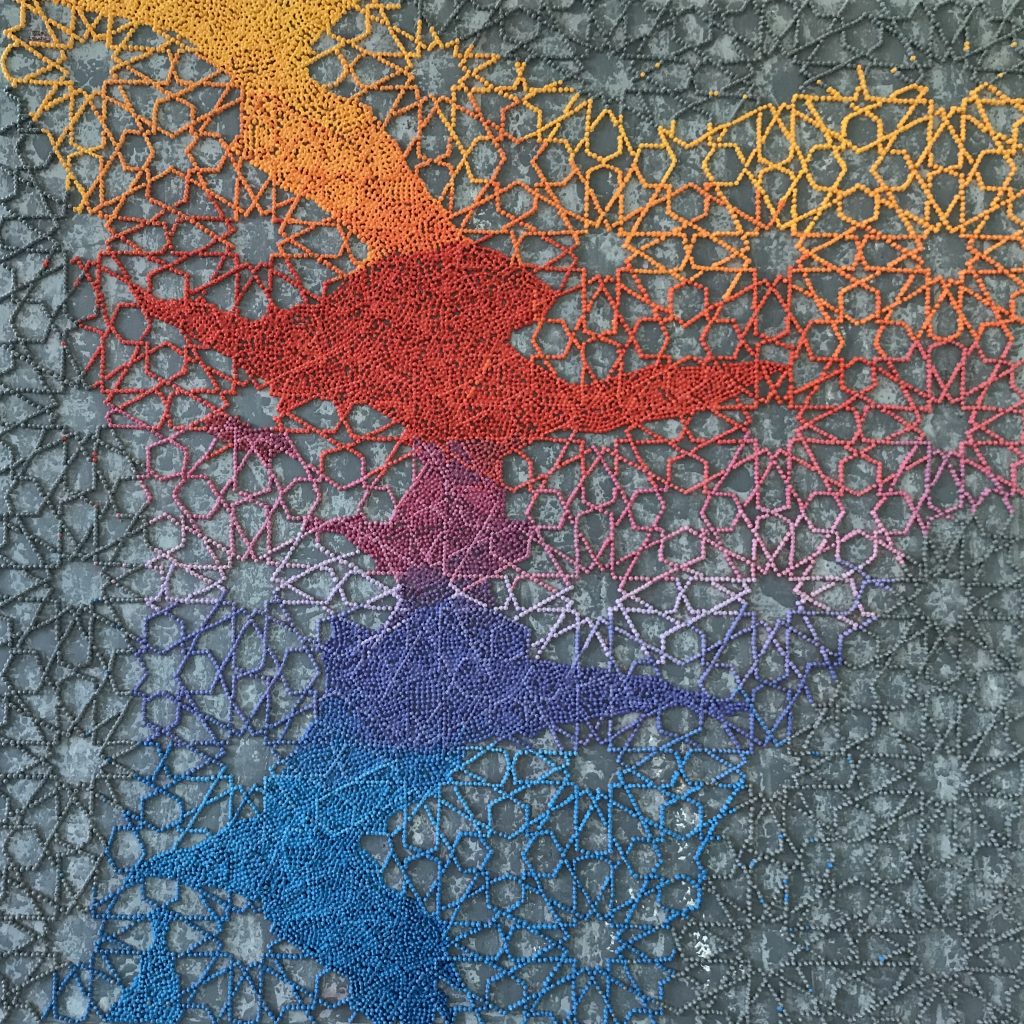

To speak about the works of Farnaz Farid, it is necessary to consider the Iranian painting tradition from a historical perspective. In her paintings, Farid establishes a powerful relationship between ornamentation and abstraction. Rather than incorporating Iranian visual culture as a direct quotation, she carries it into the work as a structural mode of thinking. Read through geometric order and the Islamic ornamental tradition, these works depart from traditional materials and techniques, opening the painting process to experimental applications.

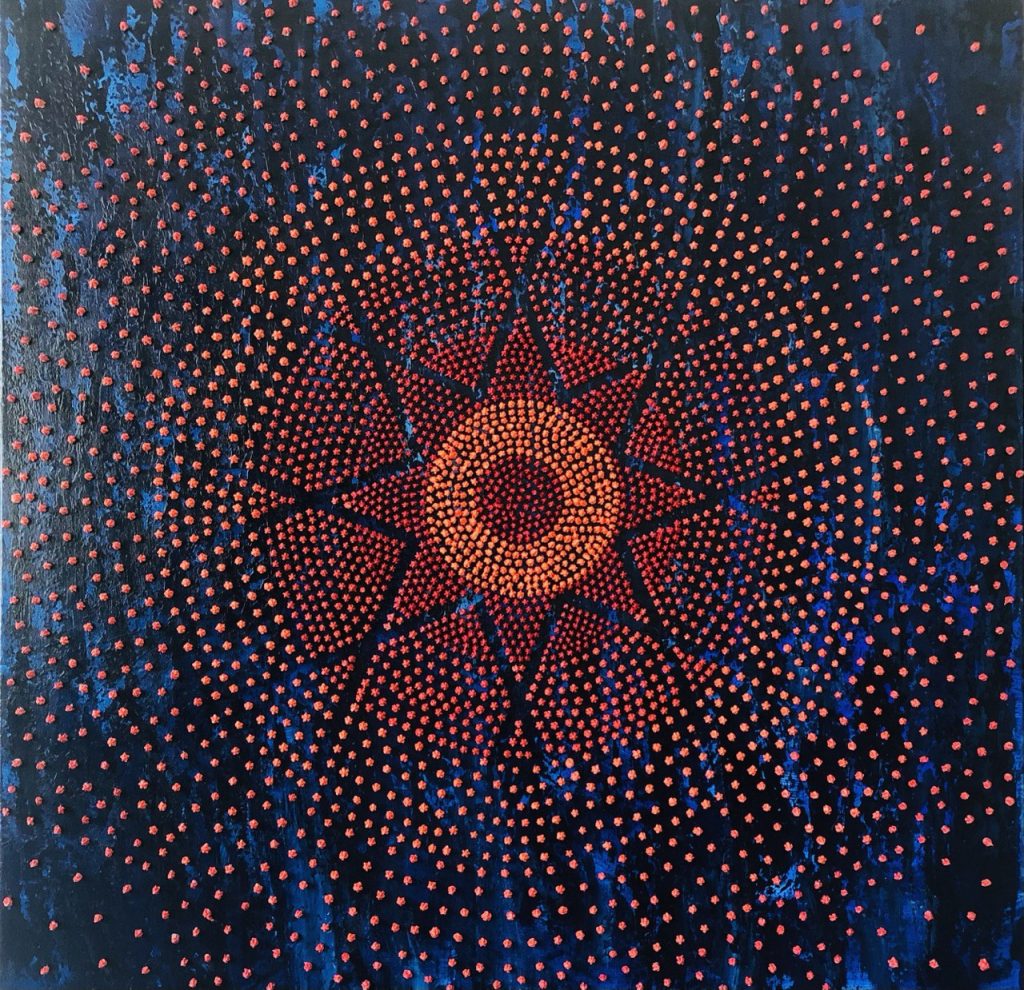

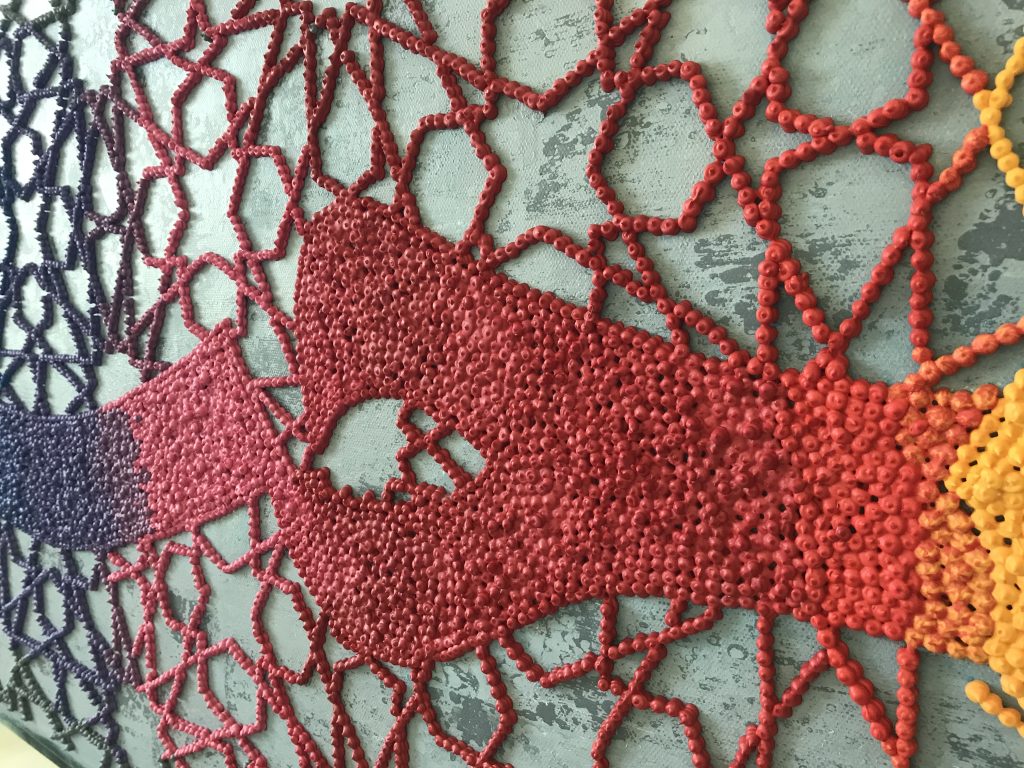

A defining element in Farid’s practice is the girih and star-based geometric networks characteristic of classical Iranian–Islamic art. Traditionally grounded in ideas of infinity, repetition, and cosmic order, these patterns are rendered here not with mathematical perfection but with a pronounced sense of the handmade. Subtle deviations, variations in texture, and the material presence of paint humanize the geometric system. The sedimentary and volumetric placement of paint introduces a minimal plastic depth, while the act of painting itself takes on a constructive, almost architectural character. In this way, Farid creates a contemporary rupture from the sacred and idealized forms of tradition.

Compositions structured through repeated and articulated motifs evoke Seljuk ornamentation and the Arabic–Persian calligraphic tradition. Calligraphic forms appear not as legible text but as gestural traces. Writing relinquishes semantic meaning and becomes a visual rhythm, producing an intermediate space between linguistic identity and abstraction. This condition resonates with the tension between identity, expression, and silence that frequently emerges in the work of contemporary Iranian women artists.

Compositions structured through repeated and articulated motifs evoke Seljuk ornamentation and the Arabic–Persian calligraphic tradition. Calligraphic forms appear not as legible text but as gestural traces. Writing relinquishes semantic meaning and becomes a visual rhythm, producing an intermediate space between linguistic identity and abstraction. This condition resonates with the tension between identity, expression, and silence that frequently emerges in the work of contemporary Iranian women artists.

Farid’s color palette—turquoise, yellow, deep blue, red—recalls the chromatic language of miniature painting and tilework. Yet through experimental applications and a tactile relationship with paint, color functions structurally rather than decoratively. In several works, interventions disrupt the continuity of the surface: scraped, covered, or eroded areas emerge. These gestures shift the painting from an idealized ornamental surface toward one marked by historical memory. Time becomes palpable, oscillating between what appears on the surface and what remains embedded beneath it.

At moments, ornamentation resembles fragments uncovered from beneath a wall, intensifying sensations of erosion, intervention, and duration. This visual strategy suggests tradition as a living, mutable entity—one that transforms rather than remains fixed or confined to the museum.

Farid neither romanticizes her cultural heritage nor treats it as a nostalgic decorative language. Instead, within the interplay of ornament and order, surface and intervention, script and suspended meaning, she approaches tradition as a contemporary field of thought.

While her works may initially recall Bauhaus aesthetics, they fundamentally diverge from them. In the Bauhaus tradition—exemplified by artists such as Klee, Kandinsky, and Albers—geometric form is understood as universal, detached from history, locality, and cultural specificity. Geometry functions as a rational, functional, and culture-independent visual language. In Farid’s work, this logic is reversed. Geometry becomes a carrier of cultural memory: historically charged, ritualistic, and cosmological as much as mathematical. It is neither purely decorative nor functional. Within Islamic ornamentation, geometry operates as the earthly manifestation of divine order.

While her works may initially recall Bauhaus aesthetics, they fundamentally diverge from them. In the Bauhaus tradition—exemplified by artists such as Klee, Kandinsky, and Albers—geometric form is understood as universal, detached from history, locality, and cultural specificity. Geometry functions as a rational, functional, and culture-independent visual language. In Farid’s work, this logic is reversed. Geometry becomes a carrier of cultural memory: historically charged, ritualistic, and cosmological as much as mathematical. It is neither purely decorative nor functional. Within Islamic ornamentation, geometry operates as the earthly manifestation of divine order.

Thus, the rational order of Bauhaus transforms here into a metaphysical one. Despite surface similarities, the layers of meaning differ profoundly. The flawless modernist surface gives way to one that is intervened, worn, and marked. Patterns appear suppressed, erased, or later recalled. The presence of manual labor and chance is made visible. This approach resists modernism’s narrative of progress by allowing the sediment of time to remain embedded within the image.

A critical issue in these works is the question of ornament. Western modernism long relegated ornament to a secondary position, famously declaring that “ornament is crime.” Farid challenges this hierarchy by revealing ornament as an intellectual and conceptual structure. Rather than rejecting ornament, her work transforms it into a philosophical space. In this sense, her practice consciously—or unconsciously—reverses Bauhaus aesthetics. Ornament here is not merely an aesthetic choice; it operates as a visual metaphor for the historical construction of the female body.

Within Iranian–Islamic visual tradition, ornament is omnipresent yet rarely a subject. It fills the surface without producing narrative—beautiful, but silent. This condition parallels the cultural positioning of the female body: visible, yet voiceless; represented, yet denied subjectivity. By placing ornament at the center of her work, Farid transforms what has been relegated to silence into an active subject. The female body asserts its presence by adopting the visual language of the very system that renders it invisible.

These works are quiet, yet deeply political. They do not rely on slogans or overt gestures of resistance. Instead, they transform silence itself into a political language. Farid invites the viewer to think of ornament as body, redirecting the gaze, equating body with space, and withdrawing figuration from the center.

In her paintings, the body appears and disappears, yet is never absent. It is dispersed across the surface, embedded within pattern. The aim is not to erase the body, but to expand it—allowing it to occupy space differently. This may underlie the dimensional, layered presence of color across the pictorial surface. By transforming the body into space through ornament, suspending representation, and inviting an inward gaze, these paintings function as sites of contemplation.