[ad_1]

One small step backward for man, one giant leap backward for kind men.

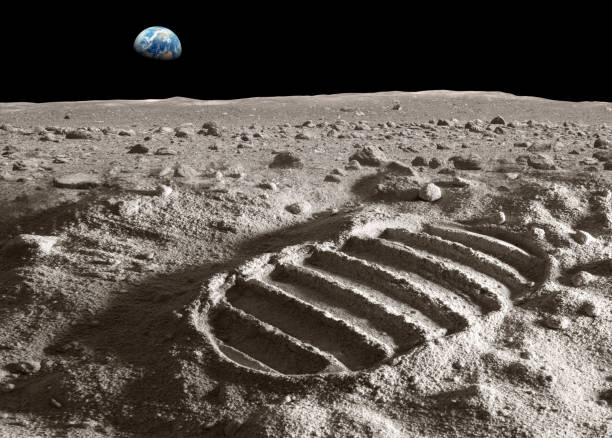

Inverting the famous words Neil Armstrong uttered after walking on the moon a half century ago feels appropriate in the aftermath of the Will Smith slap heard ‘round the world.

For many years, I led batterer intervention groups, working with men either mandated by the courts to address their domestic abuse issues and others who were “mandated” by their partners to get help or get out. Group leaders regularly heard men reluctantly admitting—or actively denying—that they’d abused their partners. From time to time there’d be stories not too dissimilar to Will Smith’s: physically and/or verbally assaulting someone they knew.

In this latest Hollywood chapter of men behaving badly, there already have been a number of insightful commentaries from African American writers. My focus is on the impact the incident may have on the ongoing work of redefining masculinity. I’m worried that the slap has already harmed the antisexist men’s movement and will embolden more men to enact violence. I’m also concerned about the message it sends to boys.

Will Smith didn’t call out Chris Rock backstage; he assaulted him in the full glare of the Academy Awards klieg lights, before a global television audience of millions. With one slap, the acclaimed movie star threatened the fragile progress of not just the batterers’ intervention movement. Group leaders only have 30 or 40 weeks to teach men how to undo 30 or 40 years of male socialization. How tragic that Smith didn’t simply comfort his wife—and turn the other cheek, rather than slap Rock’s.

Smith grew up with a father who regularly beat his mother; him, too, sometimes. “When I was nine years old, I watched my father punch my mother in the side of the head so hard that she collapsed,” he wrote in his 2021 autobiography. “I saw her spit blood. That moment in that bedroom, probably more than any other moment in my life, has defined who I am.”

Smith was doubly traumatized, first by the violence he witnessed, then by not doing anything to stop it—even though he was only 9! Male socialization’s grip is so strong that even at that young age he’d gotten the message that boys are responsible for protecting women, especially moms. Does that context, that “explanation” help us to understand why he assaulted Rock? Sure. Still, there is no excuse for his violence. But knowing about his childhood makes it easier to understand what he might have been thinking: “I didn’t protect my mother; damn right I’m gonna protect my wife.”

It was only a handful of years after Armstrong’s 1969 moonwalk that a small number of men, inspired by the insights of the powerful, nascent women’s movement, began reevaluating their notions of manhood and, by extension, masculinity. In the decades that followed these men, known as “antisexist” or, goddess forbid, “profeminist,” began rejecting conventional expressions of manhood—tough talk, stoicism and, all too often, violence. Instead, over time, they began listening to women, being vulnerable, and replacing confrontation with collaboration.

Today, this movement is global, working to transform patriarchal masculinities and rigid, harmful norms around “being a man.” It collaborates with men and boys and women on gender justice issues through intersectional feminist approaches, and develops programs in partnership with and accountability to women’s rights, gender equality and other social justice movements. There were stumbles along the way, but these men were determined to leave the old masculinity “in search of the new compassionate male,” as a podcast launched by a former Marine a couple of years ago puts it.

Not long after slapping Rock, Smith was back onstage receiving the Oscar for best male actor. In emotional remarks, he suggested that a “higher power” was inviting him “to love people and to protect people and to be a river to my people.” A wonderful aspiration, but hardly attainable if that river has blood in it.

The following day, Smith posted an apology to Rock, saying in part, “Violence in all of its forms is poisonous and destructive…I was out of line and I was wrong. I’m embarrassed and my actions were not indicative of the man I want to be. There is no place for violence in a world of love and kindness.”

His admission that his actions “were not indicative of the man I want to be” appears heartfelt. Now, what? I hope Will Smith continues the painful growth work of examining his childhood wounds as both witness to and victim of his father’s violence.

Perhaps then he’ll decide to leverage his celebrity to advance the efforts men are making globally to stop men’s violence and transform masculinities into “a world of love and kindness.”

Doing so would infuse new meaning into Neil Armstrong’s unforgettable line, “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

About the Author: Rob Okun (rob@voicemalemagazine.org), syndicated by PeaceVoice, writes about politics and culture. He is editor-publisher of Voice Male magazine.

[ad_2]

Wow, wonderful weblog format! How long have you been blogging for?

you made blogging look easy. The total look of your web site

is wonderful, as smartly as the content material!

You can see similar: sklep internetowy and here sklep internetowy

Very good information. Lucky me I found your website by accident (stumbleupon).

I’ve bookmarked it for later! I saw similar here: dobry sklep and also

here: ecommerce

Howdy! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with SEO?

I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m

not seeing very good results. If you know of

any please share. Kudos! You can read similar article here:

Najlepszy sklep

It’s very interesting! If you need help, look here: ARA Agency