It’s the late ‘80s in New York City, graffiti is the omnipresent art, Run-DMC is coursing through boomboxes at block parties from its birthplace in the Bronx to Brooklyn, and off-the-rack fashion isn’t quite delivering on the vibe without the need for a remix.

Several of the young, gifted and Black had already been stepping into Dapper Dan’s in Harlem to see the designer give their fits more flavor — but April Walker wanted something for her borough and her community to call its own.

More from WWD

- A Closer Look at the Costumes in ‘Bupkis’

- A Closer Look at the Fashion in Netflix’s ‘You People’

- All the Pieces from the Palace and Juergen Teller Capsule Collection

And hip-hop was the thread that wove through it all.

Now, as the musical genre that became much bigger than artists and albums turns 50, hip-hop’s longstanding influence on fashion is clear — but what’s at times still fuzzy is the female influence. This Juneteenth, WWD celebrates their stories.

Some key women were shaping styles that would become iconic and go on to help define the streetwear we know today. Walker, founder of Walker Wear, was one of them; the music was her muse.

“I reverse engineered into fashion because of my love for hip-hop. It was the soundtrack of my life at the time,” said Walker, who’s regarded as the first woman, and among the pioneers, in what’s now known as streetwear. A new documentary short by NBC News out Thursday, “50 Years Fly: The Rise, Fall and Revolution of Hip-Hop Fashion,” has Walker among its interviewed experts.

That hip-hop soundtrack was big and the clothes would be, too.

“Public Enemy was a huge influence and there was everybody from Chubb Rock, Audio Two, Run-DMC, a lot of people I was listening to. And even before that, coming up with Grandmaster Flash and all of those guys, they were really talking about neighborhoods and concerns and things — they were like the CNN but for the streets, things that weren’t being talked about on the news,” Walker said. “So, it really spoke to my heart and the energy was magnetic, and New York was just a magnetic and electric vibe in the ‘80s. You had this whole Reaganomics and crack era setting in, and at the same time, there was this spirit of entrepreneurship going on with people figuring out how to actually create. It was an innovative time for us.”

She started with her first custom clothing shop, Fashion in Effect, in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, but used the streets to inform her next move.

“The club scenes were crazy. We had Latin Quarter at that time, we had Broadway International, Barnes International, Zanzibar, Bentleys, Roxy…those were like fashion shows for me,” Walker said. “I was able to see people in their best forms of self-expression, but they were actually self-expressing by manipulating and remixing styles that they went and bought off the rack but wasn’t really representing lifestyle for us of that moment, of what we were hearing, feeling. We were bleaching our jeans, ripping up our shirts and just doing things a little different. That’s what hip-hop is to me.”

Before long, after popping in at Dapper Dan’s and thanks to her Fashion in Effect customer base who knew what they wanted from style, Walker Wear was born.

“I officially started Walker Wear because I started styling. And my first styling was with a group called Audio Two and Audio Two came in the [Fashion in Effect] store one day — I think MC Lyte referred Audio Two — because they wanted someone from Brooklyn to make the clothes for their video,” Walker said. Her work ended up on the cover of the duo’s “I Don’t Care” album. “I knew nothing about styling. This was way before styling companies like June Ambrose and Mode Squad and all of those guys really existed. At that time, you had to fight for any kind of styling as an artist, especially in hip-hop because it was so new.”

But Audio Two wanted Walker to style their next video, and things carried on from there. Before long — and by then 1989 — Walker Wear’s first key piece, the Rough and Rugged suit, had hit the scene. It was a 14-ounce bull denim jacket and pants set that also came in raw and washed denim.

“It was really formed out of necessity and listening to customers and what they wanted: deeper pockets, more leg room, they wanted their bottoms to go inside of the Timberlands or outside and just fit,” she said of the suit.

New York’s grit and the era’s rebellion against oppression (not dissimilar from the Black Lives Matter movement) also colored Walker Wear’s designs. The death of Michael Stewart as a result of police brutality after an arrest for writing graffiti on a New York City subway wall was among the higher profile provocations. The same way hip-hop put what was happening into the music, Walker put it into the clothing.

“We wanted to carry that spirit but I wanted to represent and talk about it,” she said. “So it really started with airbrushing and using fashion as canvases with acrylic art and different things like that. Then we would custom make anything from velour sweatsuits, raw denim and then our basic fleece.

“And we really tapped into New York because New York was our flavor at that time and that’s what we were focused on. And the vibe in New York, think Carhartt, think Timberland 40 Belows, denim, leather gooses, shearling, medallions, all of these things existed….My marriage was combining workwear and fashion to meet function, and really I wanted to create something timeless and classic and really focused on quality, so that’s where it started. Brands like Carhartt, Willi Smith from the fashion sense, he was a Black designer I wore in high school and the only image that I really had of a person of color, really influenced me. And then Dapper Dan and his hustle meeting the streets. All of those things created a perfect storm for me to want to step in and create uniforms for our tribe.”

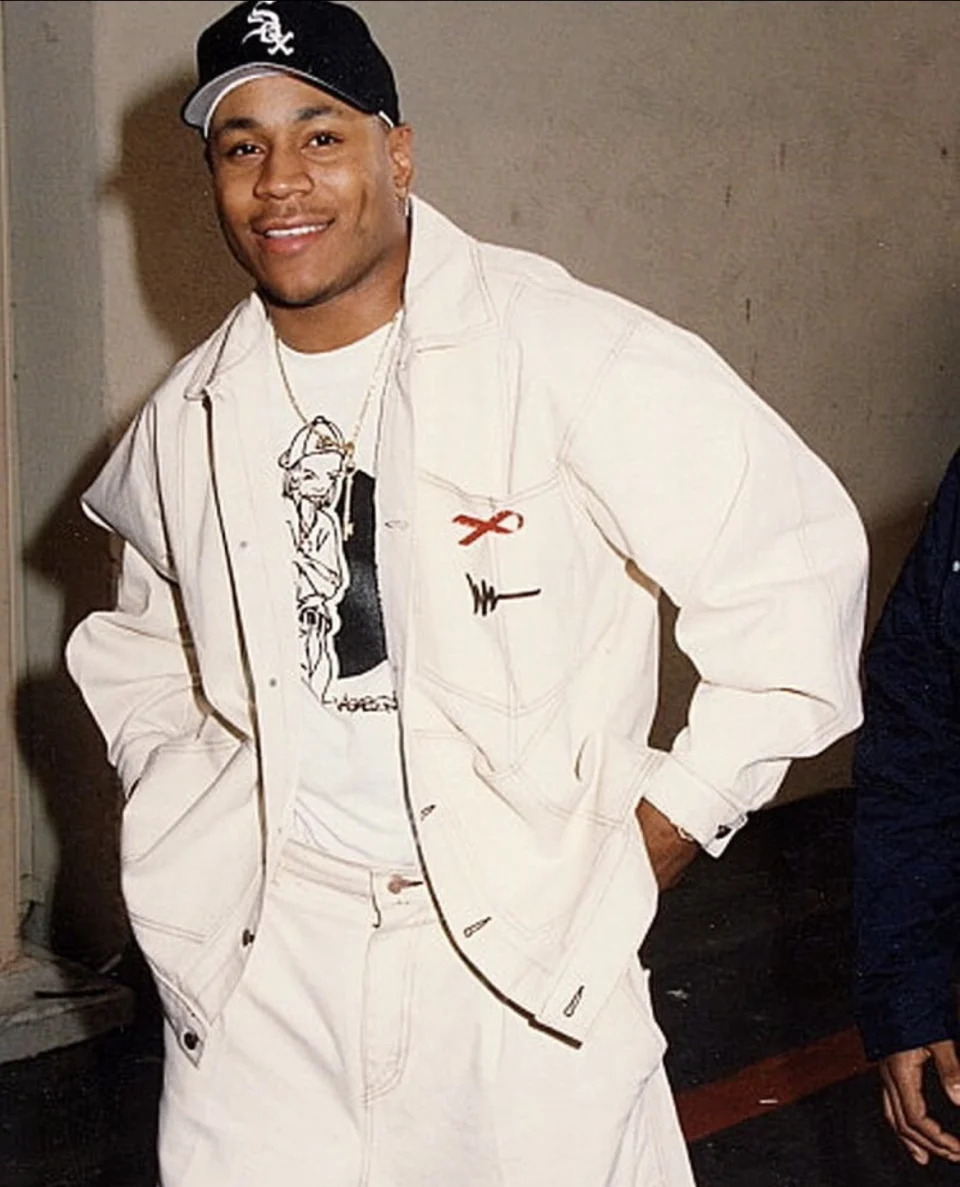

As Walker Wear’s popularity grew, Walker dressed and styled artists from Tupac to Notorious B.I.G., Queen Latifah to LL Cool J, and many in between. Beavis and Butt-Head even wore Walker Wear.

“My dad was working with Jay-Z at that time, he was in the music industry, so Jaz-O [Jay-Z’s mentor at the start of his career] and Jay-Z were big amplifiers for me,” she said. “Guru moved across the hall from me when he first came from Boston to New York so he was my actual neighbor, I gave his first demo to my dad and that’s how I started working with Gang Starr, once him and [DJ] Premier got together. It was like Easy Mo Bee lived next door to me, he was in the next building.

“One day Stretch came on set with Tupac — and this is still like ‘89 and at that time, he was still a roadie and working with Digital Underground, but that’s when ‘Same Song’ [a track by hip-hop group Digital Underground featuring Tupac] was really coming out and that’s how I got to start styling Pac. It was like all these little pockets grew and he did that album with Easy Mo Bee, like literally we’d all see each other all the time. It was a time when we were all growing and exchanging ideas,” Walker said. “It wasn’t these six to 10 layers to get to a person because we were all young, no one believed in hip-hop at that time like we did. It wasn’t this multibillion-dollar industry yet so we were still on some against the grain, let’s do it, whatever it was and I think [we were too] naïve to fear. That’s what enabled us.”

But even with all that visibility, however underground at the time, Walker stayed out of the spotlight largely because she was a woman. The industry, like the music, didn’t hold women in high regard.

“It was a misogynistic industry at that time because hip-hop music was so misogynistic when we went into the beginning of the ‘90s,” Walker said. “It wasn’t this #MeToo time and women’s empowerment time, so I decided to let the product lead and to play the background.”

She skipped doing interviews and opted for product placements with musician and DJ Jam Master Jay, rappers like Treach and Method Man and groups like Naughty by Nature.

“I just remember people were like, ‘Is that Treach’s line?’ And that was intentional to A, distract, and to B, product place to get the brand out there,” Walker said. “That was my advertising, but it was also to make sure that it didn’t fail because people thought a woman was behind it and I wasn’t sure about that at that moment.”

Though it’s somewhat of a small list of women who influenced fashion through hip-hop, their contribution was big when it comes to creating iconography and impacting pop culture.

“When I think about sculpting and people that shaped the images, because I think that was, in the beginning, [affecting culture] a lot more than the brands [were], Sybil Pennix was a great stylist, she worked with Bad Boy and a lot of their artists. Then I would also say Misa Hylton [who styled Lil’ Kim and Mary J. Blige, among others] was another architect that did amazing work,” Walker said. “[There’s also] Dionne Alexander, who doesn’t get enough recognition. If you look at a lot of Lil’ Kim’s wigs, those infamous wigs…she worked with a lot of people and worked with their images, what you know today. I would say June Ambrose [currently creative director of Puma, as well as the stylist who created Missy Elliott’s highly memorable look in the music video for her hit song, ‘The Rain’], she was definitely a staple in terms of when we think about hip-hop style.”

At Fubu, perhaps the most notable of the O.G. streetwear brands, even though entrepreneur and designer J. Alexander Martin and cofounders Daymond John, Keith Perrin and Carl Brown were at the helm when the label launched in 1992, Kianga “Kiki Kitty” Milele, was the head designer at the brand for seven years at its height.

Some, like Milele, might have played behind the scenes while others were more prominent.

A WWD article from June 8, 2000, titled “Designing Women” featured Lisa Miyakado, designer at Lady Enyce, the womenswear partner to menswear label Enyce, and Camella Ehlke, who founded Triple 5 Soul. Kimora Lee Simmons, the creative behind Baby Phat, was also in the story. WWD wrote at the time, “Using a sleek cat as its logo, Baby Phat has grown from baby Ts to a full collection of denim sportswear, lingerie and accessories, projecting $40 million in sales in 2000.”

At the age of 13, Lee became one of Karl Lagerfeld’s muses at Chanel — he had called her “the look of the 21st century.” She even landed herself a coveted spot as the youngest couture bride to close the house’s haute couture shows during her first season in Paris.

When Lee Simmons took the helm at Baby Phat, a breakoff, but individual business endeavor stemming from her then-husband Russell Simmons’ Phat Farm, she made it her mandate to bring elements of her couture runway past to the oversize signature that had settled over both men’s and women’s clothing in the hip-hop scene. She brought glamour and streetwear together. And when Baby Phat’s first solo show took place at Radio City Music Hall during New York Fashion Week in 2000, so began the love story between high fashion and the clothes that came up with hip-hop.

“We were influenced very much by music and very much by some of our artists at the time and contemporaries. But Baby Phat was very much setting the tone there because it’s breaking away from the men’s establishment,” said Lee Simmons, who also appears in “50 Years Fly.” “It was trying to turn it in a different direction, and trying to celebrate the sexiness and the femininity of a woman.”

The marriage between the music and the fashion created a vibe that made the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

“It’s a lifestyle that we kind of articulated. And I think it permeated all aspects of life,” she said. “What was that lifestyle? Very high energy, luxury. For me, it was mixing high and low price points, elements, fashion, labels. It was about luxury. It was about everything luxe.”

By the late ‘90s when Baby Phat arrived, there were still few women visible or being recognized enough for their contributions to fashion in hip-hop.

“In a lot of ways, women are overlooked and pushed to the side and you have to play a part, you have a role, and it’s very often suppressed. And I’m not trying to sound in any kind of way begrudging, I’m just stating what it is,” Lee Simmons said. “We’ve come so far as women of color in fashion, but obviously we still have so far to go. I think a lot of these things ring true in politics, education, banking, finance, doesn’t matter…in our family life, in hip-hop and fashion, but it rings true in many, many different areas over and over again.”

What also rings true, whether adequately credited to the women who contributed or not, is that hip-hop has had a heavy influence on fashion over its 50-year lifespan.

“I think it’s important to show that something that began as music grew into so much more than that, a lifestyle and an outlook, an idea, a way of life, a form of revolution if you would,” Lee Simmons said. “Maybe some people thought there was an expiration date on [what’s considered streetwear today] but that expiration date hasn’t come.”

Even Baby Phat — which, for an evolving industry, seemed to have reached its own expiration date — the sentiment was premature since Lee Simmons relaunched the label during the pandemic, through partnerships with Macy’s and Forever 21. And there are plans for more from the brand later this summer. Phat Farm is back under Lee Simmons’ purview, too, and there is movement underway to give it new life.

Walker Wear is also still standing and Walker, who also now lends her expertise to education and films, wants to make sure women don’t take a backseat in their own brands or when it comes to being architects of style.

“I don’t think that women get the credit that they’re due, period. I think fashion is a microcosm for the macrocosm of our culture on a global level,” she said. But, she added, “I’m really inspired by the fearless women that are out here and so many more in our industry. When I first started there were none. There still aren’t enough that are recognized, but there are a lot now and they’re doing it and they’re doing it well.”

To those who lay claim to inventing streetwear when there were, in fact, others before them, Walker is unfazed but firm: “I think whoever has the microphone has the loudest voice. And I think that whoever controls the distribution has the loudest, loudest voice. So, until we have vertical operations where we control everything from the creations to the distribution, it’s going to be up to us to tell our own stories and to amplify them with bullhorns and to really spread those stories by contagious behavior, by sharing. And the nice thing about the internet, digital tools, they allow us to do that. We just have to be savvy and we have to be intentional and mindful to do it and share our history because if we don’t it will be told a different way, it will be erased and eradicated.

“We’re seeing it happen in schools, with books, with so many things, so it’s really up to us to really beat our chest and talk and really share so that our stories and our history does not go away. And it’s not for the sake of ego or shego, it’s for the sake of the next generation and the next generation so they can see that we were here, and if we can do it, they can do it even better.”