Take any major historical Western art movement from the 16th century through today and you can bet women played an important role. Until the last handful of years, you can also bet that male scholars writing the histories of those movements minimized their impact or omitted them all together.

Only within the past decade have they begun receiving any appropriate measure of due for their contributions.

Add Susie M. Bartow’s name to that list for the Hudson River School, the first major art movement in the United States. Founded in the mid-19th century along the Hudson River in New York by Thomas Cole, the Hudson River School was a community of landscape painters exalting America’s natural beauty.

Barstow (1836-1923) receives the first retrospective of her career one century following her death during “Women Reframe American Landscape: Susie Barstow & Her Circle,” appropriately on view at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in Catskill, NY through October 29, 2023.

No woman from the Hudson River School has ever had a solo show. Anywhere. Until now.

“When you think of the Hudson River School, you think of Thomas Cole, Frederic Edwin Church and Asher B. Durand, but the women have been erased from that history,” Kate Menconeri, Chief Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, Contemporary Art, at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, told Forbes.com.

Barstow was selected because the Cole Center had one of her paintings in its permanent collection and in researching female Hudson River School painters looking for one to highlight, exhibition co-curator and Professor of Art History at Towson University Nancy Siegel connected with Barstow’s family who still had her sketches, sketch box, paint brushes, numerous paintings, and other items from her art practice.

“While there are certain formal elements that quickly identify Susie Barstow’s painterly style—her particular brush strokes with regard to the bark of birch trees or moon-lit recesses deep within nature—it is important to see how her work rests comfortably within the style of the Hudson River School as it evolved across the nineteenth century,” Siegel told Forbes.com. “Hers are paintings that glorify and celebrate the landscape just as those by her male colleagues. In this regard, these are artists not separated by their gender, rather, the artists of the loosely-defined Hudson River School were united by their passionate quest to hike, sketch, and paint the awe-inspiring views of nature they experienced first-hand.”

Barstow hiked up to 25 miles a day–in period clothing, of course–sketching the Adirondak Mountains, White Mountains and Catskill Mountains. She exhibited and sold paintings alongside major male figures of the Hudson River School, she just wasn’t written into the history books.

“The exhibition is a deep dive on Susie’s work and also includes other painters, specifically women, who were painting in her circle,” Menconeri explains. “We know that there were over 50 women who were painting landscapes in 19th century America, so we want to bring them a spotlight and recognition.”

Contemporary Practices

“Women Reframe American Landscape” is a two-part exhibition with Barstow centering one half and contemporary women artists who focus on land and landscape in their work the other.

“American landscape painting–the paintings that we’ve been seeing–have all been by predominantly white men, so we’re only seeing landscape according to one specific group of people,” Menconeri said. “At the heart of this (exhibition) we wanted to say, ‘what’s landscape to women, not only in the 19th century, but today?’ It feels urgent because there’s so much at stake with climate change and recentering people on the land and thinking more deeply about the history of the land in the United States.”

Always remember, America was built by slave labor working stolen land.

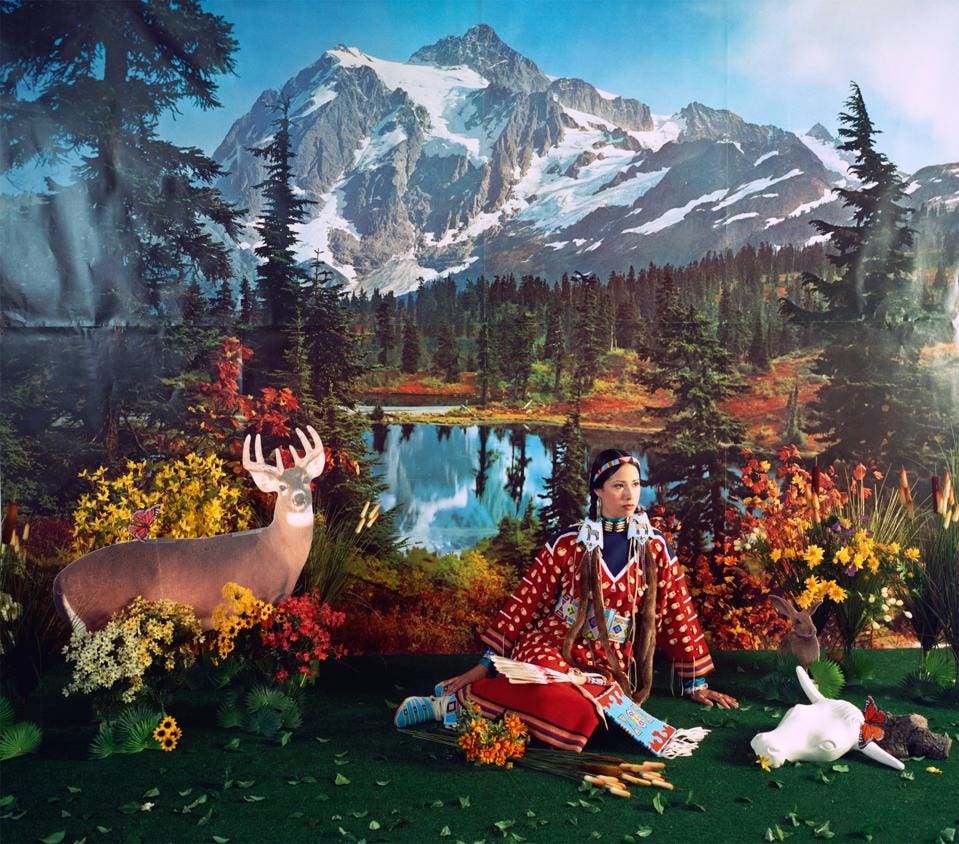

The exhibition’s contemporary works come from a powerhouse roster of predominantly African American, Native American and Latina artists including Teresita Fernández, Ebony G. Patterson, Wendy Red Star (Absáalooka), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation) and Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee).

Diverging from Barstow and their Hudson River School forebearers, they use sculpture, video, collage, photography and site-specific installations to comment on land and landscape. Examples of all are on view during “Women Reframe American Landscape: Contemporary Practices.”

“Landscape art doesn’t have to just be a canvas with a single point perspective horizon line and a gold frame; landscape is something much more complicated,” Menconeri reminded.

Much more complicated in the hands of the contemporary artists.

Their work is less representational, more confrontational. They are not coy in their expressions of how land is contested. They consider themselves more participants in the land as opposed to observers of it. They make definite distinctions between “land” and “landscape.”

Unlike the Hudson River School painters, and most 19th and early 20th century American landscape painters, contemporary artists show the land’s human side. Land not removed from people–the so-called “wilderness”–but places that have been peopled for tens of thousands of years.

Concepts of land as either natural and wild, or developed and populated, are 19th and 20th century colonial concepts. Land needn’t be either/or.

People can be integral actors in spectacular, healthy landscapes teeming with biodiversity as surely as they can be absent from vast, dead landscapes wrecked by chemical contamination, mining or bomb testing. Think of Indigenous practices, people living productively on the land in balance with nature as opposed to white, settler colonial practices of people having to be removed from land in order to protect it, lest that land be logged, mined, farmed and paved to oblivion.

That tension is the entire foundation of America’s National Park System, the belief that unless people are removed entirely from these remarkable places except to visit, they will surely destroy them, failing to recognize that Indigenous people lived on those lands for thousands of years without doing so.

Cole can be considered an early environmentalist advocating for balance between the built and natural worlds through his painting and writing. He was ahead of his time speaking out against the escalating development and deforestation of the Catskill Mountains almost 100 years ago. Railroads and tanneries and iron foundries and mills chewing up the land, the landscape, but he was oblivious to the thousands of years of inhabitation that had occurred on that land by Indigenous people who didn’t similarly threaten it.

People don’t necessarily endanger the land and landscapes, white people do. Colonizers do.

Contemporary artists make this distinction clear.

Deliciously, their artworks are sited within and in response to Cole’s artwork, home, studios, and bucolic grounds creating one compelling juxtaposition after another.

As is generally the case, the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous troupe of feminist artists, say it best in a text piece specially created for this exhibition which reads, in part: “Hudson River School Paintings depicted a wilderness tamed by white settlers; when, in fact, the land had been inhabited, cultivated and protected for millennia by Indigenous nations. While Hudson River School painters romanticized and idealized the stolen land, robber barons extracted whatever they could, and left a mess for future generations. These same tycoons bought Hudson River School paintings, donated them to museums, and promoted an Eden that never was.”

After leaving the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, “Women Reframe American Landscape” travels to the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, CT from November 16, 2023, through March 31, 2024.